Author: Minhal Mussawar, University of Saskatchewan | Editors: Romina Garcia de leon, Shayda Swann (Blog Coordinators)

Published: September 23rd, 2022

Oral contraceptives are one of the most commonly chosen forms of contraception in Canada. Reasons for this include high therapeutic value and status as a cheap and accessible form of contraceptive, but also for their health benefits, such as managing dysmenorrhea, premenstrual syndrome and reducing the risk of ovarian cancer. Hence, they represent a cost-effective way of mitigating and treating many health conditions. Unfortunately, they also come with a number of negative side effects, including nausea, headaches and cramping, and can increase the risk of cardiovascular conditions in some users. Moreover, the likelihood of developing serious complications, such as venous thromboembolisms, can vary depending on whether an individual is taking a combined or progestin-only pill, meaning that certain patient populations may fare better on one type of pill than another. Another health condition that may be influenced by oral contraceptive type is breast cancer, where women who use high-dose estrogen pills are at a higher risk of developing breast cancer than those who use lower doses.

Evidently, there is plenty of research regarding the physiological effects of oral contraceptives on its users. In an age where female participants are being studied more and the scientific community has acknowledged its history of favouring male participants in the past, this type of research has become paramount as it represents a push towards sex inclusivity in literature that was previously non-existent.

Yet, while progress has been made with respect to studying the physical effects of oral contraceptives, less can be said about their cognitive and psychological effects. One study reported mood differences associated with the use of combined oral contraceptives, and another noted differential effects on verbal memory based on whether participants were in the active pill phase (pills that contained the active ingredients of estradiol and progestin) of their birth control or the inactive phase (“placebo” pills). However, aside from generalised research on the effects of combined pills, few studies have assessed the extent birth control can impact a person’s cognitive functioning. Even fewer have separated the effects of ethinyl estradiol and progestin (the two active ingredients in all combined oral contraceptives) and independently studied their effects. Our study aimed to address this issue; we wanted to see how one component of the combined oral contraceptive pill – progestin androgenicity – can affect various cognitive and emotional parameters.

Progestin androgenicity refers to the extent to which a progestin is structurally related to the androgenic hormone testosterone; progestins with high levels of androgenicity tend to bind to testosterone receptors in the body with a higher affinity than their anti-androgenic counterparts. This, unsurprisingly, leads to more androgenic side effects when taking the pill. For our study, we first looked at the existing literature on progestin type and cognitive differences. We found a few papers that suggested users who took oral contraceptives with androgenic progestins performed worse on verbal memory tasks than those who took anti-androgenic contraceptives. Other research suggested that individuals who took oral contraceptives with androgenic progestins performed better on visuospatial and socio-emotional tasks.

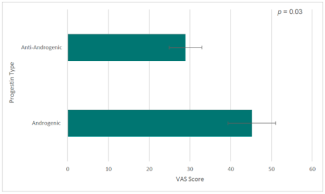

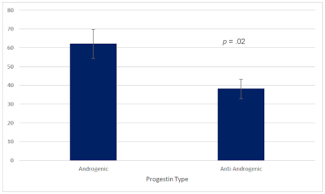

Based on this research, we anticipated that individuals taking highly androgenic progestins would yield higher and more accurate scores on social-emotional cognition (emotion recognition and rejection sensitivity) relative to non-androgenic progestin users. Our findings aligned with this hypothesis, as we found that androgenic progestin users were better at recognising negative emotions such as facial expressions of sadness, fear and disgust. Interestingly enough, androgenic users also reported feeling significantly more stressed when measuring their mood on a visual analogue scale compared to anti-androgenic users. Overall, these results indicate that highly androgenic progestins may have a negative psychological effect on users versus anti-androgenic users.

Figure 1. Progestin androgenicity effects on mean stress scores on the Visual Analogue Scale (standard error bars shown). Androgenic users reported feeling significantly more stressed throughout the lab session.

Figure 2. Average rate of correct identification (%) for sadness on the Emotion Recognition Task (standard error bars shown). Androgenic users were significantly more accurate at identifying sadness compared to anti-androgenic users.

These findings are consistent with previous research on androgenic hormones and socio-emotional cognition; studies have found correlations between social threat identification and testosterone. Additionally, anti-androgenic progestins have historically been used to treat negative mood in premenstrual syndrome; this makes the association between negative mood and androgenic progestins expected.

So how do we interpret these findings on a larger scale? Well, there are two key implications that arise from this study, the first of which comes from the association between negative mood and androgenic progestin use. As noted earlier, oral contraceptives with anti-androgenic progestins can be used to treat negative mood symptoms in premenstrual syndrome. With this in mind, it may be worth considering progestin androgenicity when prescribing oral contraceptives to this patient population, as well to patients who may be at risk or have a history of depression and anxiety as androgenic progestins could potentially exacerbate any negative thoughts they may have. The second implication comes from how oral contraceptives are viewed in general. Since they are very common drugs, it can be easy to underestimate their effects, as a result, people who may consider using them may not appreciate how much of an impact they may have on their socio-emotional functioning. In fact, it is not uncommon to hear about people “just going on birth control” once they become sexually active, and while implementing contraceptive measures ought to be encouraged, those who are considering using them should still be informed about their potential side effects. The same goes for people who expect their partners to start oral contraceptives.

This research represents the tip of the iceberg when it comes to studying the psychological effects of oral contraceptives. There are a multitude of other factors at play that should also be considered in light of this study; for example, ethinyl estradiol dose can induce its own effects on users, independent of progestin type. This is also something that we hope to look into further with our research, where our next steps involve assessing the role estrogen plays on the same parameters. We look forward to seeing the results and hope it can help elucidate the role each hormone can play.